A Donor's Story: The Rest Goes to Heaven

Published on January 15, 2015

Over the course of Gross Anatomy, students uncover clues to how their donors died. It's harder to know how they lived. Even harder to know what they believed, and what motivated them to make this gift of themselves.

Here's the story of two - Mary and Jack Crouch, a married couple from Poplarville.

She was born on June 14 - Flag Day.

"I have my very own birthday song," she said. "Stars and Stripes Forever."

Shortly after World War II, her family moved to Cotton Valley, a town in north Louisiana adorned with a creek and a spirited young fellow named Jack.

"The creek was just past where my family lived," she said. "The Crouch family lived up the hill a little way. I always said I was from the right side of the creek and Jack was from the wrong side.

"When he was 16 he said he got 'tired of daddy telling me what to do.' So he went to New Orleans and enlisted in the Marines. He survived some of Korea's bloodiest battles.

"The contrariest person in the world is a man who is a husband who is a Marine. I will have so many stars in my crown, I won't be able to hold my head up."

But before Mary and Jack got together for good, she met another man. They married, moved away and had a son. Her first husband died in 1959, killed in a traffic accident one night on the way to work.

After leaving the Marine Corps, Jack held a couple of different jobs, including motorcycle police officer in Shreveport, working security details for Elvis Presley, who was getting his start at the Louisiana Hayride.

He laid pipe after that, working all over the South. He got married and became the father of three before his divorce.

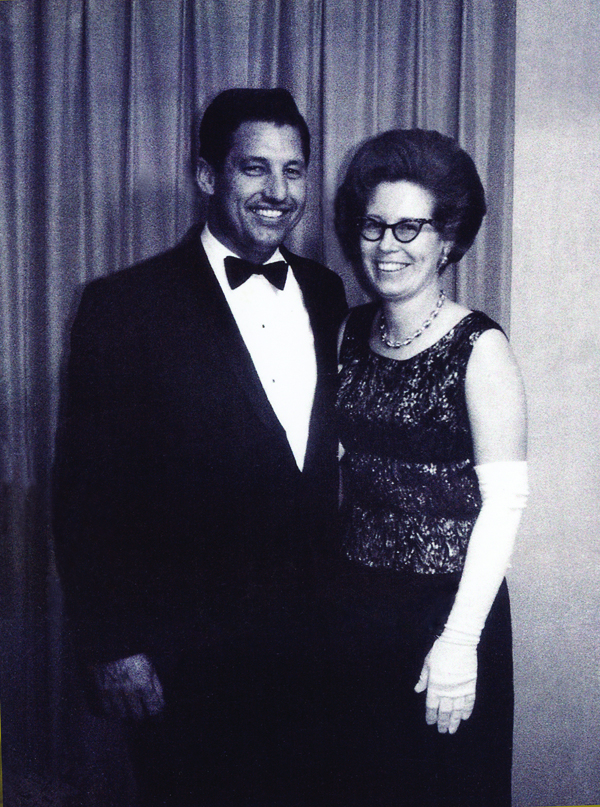

Mary and Jack Crouch in the early 1970's

For her part, Mary had moved back to Cotton Valley and worked as a clerk in a family grocery store. One day a young pipe-liner, who came home to visit his parents, walked into the store to buy cigarettes.

“That’s how Jack and I got back together,” she said. In 1963, they married.

Throughout most of their marriage, Jack kept his memories of the war to himself, sucking up the misery with the cigarette smoke.

“The doctors told him that cigarettes and welding were about 50-50 the cause of his COPD,” she said.

Later, he served as a captain on Halliburton’s service ships until 1983, when the oil industry tanked and he was laid off. He started his own engraving business .

Mary, in the meantime, had worked as a bookkeeper, co-owner of a floral shop and as a data processing clerk.

In New Orleans, where Halliburton had moved them, Jack was elected as the Grand Secretary of the Masonic fraternity for the state of Louisiana in 1985, she said; Mary worked as data processing clerk and later as office manager.

“He tried for 30 years to get me to call him ‘boss,’” she said, “and he finally succeeded.”

They retired on Sept. 30, 1999 and moved to Poplarville, where their son and his family lived.

A year or two later, they made their decision to become donors.

“Jack had emphysema; he would not get any better,” she said.

She is 82, and expects to live well into her 90s.

“God blessed me with such good health, but I’m afraid one day he’ll say, ‘OK, Mary, I’ve let you go long enough. Here it is.’ ”

There were no religious qualms about their decision to become donors, she said. “It didn’t come up. We are Baptist. What would be the problem?

“I have everything God gave me except a few teeth, and I still have most of those. So I figure, somewhere down the line, someone can use me.” So did Jack.

“The rest of me is going to heaven anyway,” she said.

They ended up with nine grandchildren and two great-granddaughters: Megan, who’s almost 7 now, and Karen, 9, who call them “Nana” and “Poppy.”

“They love that Poppy,” Mary Crouch said. “He would take time with them, even when he was sick.

“It was a very interesting life for the two of us. We traveled to Canada and, I would venture to say, half the states, including Alaska and Hawaii.

“He went into the hospital a couple of weeks after we took our Megan and Karen to the fair. We had no idea how sick he was. He didn’t want us to worry – that’s a husband, man and Marine.

“I said, ‘Honey, I ask you how you feel and I can’t get a straight answer; I don’t know how to help you.’

“He just got tired of fighting.” He died on Nov. 2, 2013 at the VA hospital in Biloxi.

Before the funeral, their great-granddaughters saw him one last time. As they were leaving the hospital, Karen said to Mary, “‘I know he’s in heaven; we just can’t see him.’”

Mary told her they’d pretend he had gone to Hawaii.

“Karen said, ‘No, we’ll pretend he has re-enlisted in the Marines.’”

The memorial service was on Dec. 7, 2013, Pearl Harbor Day. There was a Masonic graveside service and Marine honor guard at First Baptist Church in Poplarville.

“Karen gets up, marches to the piano and plays How Great Thou Art,” Mary Crouch said.

“Then she comes back, sits down and says, ‘Nana, I saw a Marine crying.’”

HOW TO BECOME AND ANATOMICAL DONOR

The men and women who have donated their bodies are memorialized in an annual Ceremony of Thanksgiving like this one, held in the UMMC Cemetery.

Complete authorization forms, which can be requested by contacting Dr. Allan Sinning, asinning@umc.edu, or Dr. Marianne Conway, mconway@umc.edu. Or write to the Director of the Anatomical Gift Program, Department of Neurobiology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 N. State St., Jackson, MS 39216. Or call 601-984-1649.

Sign the forms in the presence of two witnesses, which will satisfy legal requirements governing such gifts.

Inform your family, friends, physician and attorney of your decision to make sure that your wishes are met.