We’ve come a long way, baby

Published on December 09, 2014

You remember the searches in the sky, hunting from the helicopter for the hospital until the landmarks loomed below: the old silos and the big hamburger joint across the street.

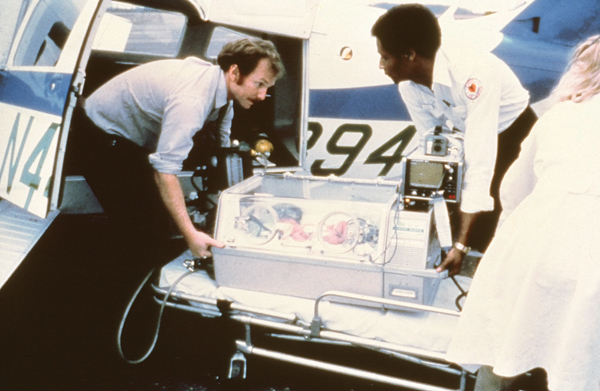

Transport nurse Kay Sucier watches an infant from her seat aboard a fixed-wing aircraft while enroute to Children's Hospital. Aircraft often were used in the early days of the transport program.

You remember stalking many more on the ground in other towns, the ambulance plowing over slippery back roads when the interstates were iced shut; or driving toward black skies cradling infant storms.

You remember hauling the incubator with the child inside, slogging some 300 feet across a yard of soupy mud where the ambulance couldn’t go and where the parents waited to get their baby back.

This is your personal history, but it’s also part of a larger story – the story of neonatal transport at UMMC, the struggles and risks, but also the things that kept you and your colleagues going: the Christmas cards from parents, the intimate expressions of gratitude from people who did not know how to thank you enough.

“There was a grandfather of a child we transported, and I told him I love blueberries,” said Jamie Miller, who retired in May after almost three decades as a neonatal transport nurse.

“Well, he grew blueberries; so one day he showed up with a five-gallon can. I shared.”

It’s been that way since the neonatal transport service’s beginnings. The technology may have changed, but the rewards haven’t. The biggest are the lives of the children.

“You remember them forever,” said April Davidson, a flight/transport nurse.

The Medical Center's original helicopter, Lifestar, was in service from 1983-1990.

“There’s no better feeling than to run into a mom in the hallway here and have her give you a hug and thank you, and it could be a year after you took care of her baby.”

Saving the life of a baby born too soon, or too sick, often depends on being able to move it to a place that can best take care of it. In Mississippi, that frequently means moving the baby to UMMC – by ground ambulance or helicopters fortified with equipment to help it survive.

The neonatal transport team here works at Batson Children’s Hospital and the Winfred L. Wiser Hospital for Women & Infants, a team that includes a neonatal nurse practitioner and nurses with special training in transport and neonatal intensive care.

They are the only ones available 24/7 in a state that has the highest rate of premature births in the country: 17.1 percent, as reported by the March of Dimes last year.

This team counts on support from respiratory therapists, registered nurses and paramedics, along with UMMC physicians with training in neonatal and pediatric intensive care who handle referrals and stay in touch with the team on its journeys.

Transport teams at UMMC and elsewhere are “delivering state-of-the-art care,” reported Pediatrics, the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics, in July 2013. “Evidence shows such teams improve patient outcomes.”

Jamie Miller

Using the oldest records she could find, Miller counted the babies – many of them preemies – her unit cared for and transported. The number is well more than 10,000 – enough babies to rival the populations of, say, Indianola, Petal and Picayune.

Miller, who began working in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in 1983 before becoming a member of the transport team a couple of years later, helped move 4,000 of them – almost three times the population of Sharkey County in the Delta, the region where many of them came from and were returned whole.

“We never turned away anybody,” she said. “Ever.”

A moving delivery

It’s hard to overestimate neonatal transport’s impact on the health of newborns, not to mention on the emotions of their parents.

Beth Mullins

One particular dad may have summed it up when he took Beth Mullins aside and said, “You made us feel safe on the worst day of our life”

“You make a huge impression on them,” said Mullins, nurse practitioner and neonatal transport coordinator, “because their baby is in your hands.”

Until four decades ago, there really wasn’t anyone the parents of these babies could turn to, especially in rural areas. That’s when the concept of neonatal transports at UMMC began.

But, before that could happen, there had to be a reason to move a premature baby – that is, some hope that it would do any good. The truth is, until relatively recently, premature, or early-term, babies often didn’t live long.

To be considered full-term today, babies must be born between 39 weeks and 40 weeks plus six days after conception, a guideline endorsed in 2013 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Formerly, the span was thought to be between 37 and 42 weeks.

Even at 37 weeks, newborns have a higher risk of complications, particularly difficulty in breathing, reported a 2010 study conducted at the University of Illinois in conjunction with the Consortium on Safe Labor. These babies also have trouble staying warm.

At the turn of the 20th century, a baby born only a week or so early rarely made it. It wasn’t until the 1920s that a hospital in Chicago created a station to care for premature infants; in this country, that marked the start of hospital-based intensive care for preemies and low-birth-weight babies.

The standards of care advanced at a crawl. Administering oxygen to the babies helped, as did early incubators, although they were notoriously fickle.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that the country became mobilized, touched by the tragedy of one certain child: the son of President John F. Kennedy and his wife, Jackie. The boy was born 5 ¹/2 weeks early, at 4 pounds, 10 ¹/2 ounces. His premature birth, and death, in 1963 hit home with many Americans.

In 1960, a 1-kilogram (slightly more than 2 pounds) newborn had a 95 percent chance of dying, reports Stanford University’s Department of Pediatrics

For the next 40 years or so, one innovation after another saved lives – although, Mullins said, “a 4-pound baby was a miracle, even 20 years ago.”

Now, almost any baby who lives through birth has a chance, if given the proper care.

By 2000, a 1-kilogram baby had a 95 percent chance of survival, Stanford University reports.

Today, some surviving babies weigh in at around 1 pound, about as much as a loaf of bread. Some are born about four months too early, but must stay about that long, or longer, in intensive care. They are chronically ill and have birth defects.

The Neonatal Cradle, one of the earlier ambulances in the transport fleet, was donated in 1979 by the Junior League of Jackson.

“We’ve had babies who have been here more than a year,” Mullins said. “We have birthday cakes sometimes.”

“The staff gets attached to them,” Davidson said.

Miller certainly did. “The ones I remember are the ones I stayed in touch with,” she said.

“There was a baby I picked up who had a heart defect. I got Christmas cards from the family a long time afterwards. Unfortunately, he died when he was 4. I still have a picture of him in my bedroom.”

Still, the longer she worked, Miller, along with her co-workers, saw more and more of these babies go home and grow up. Even the ones whose problems had nothing to do with being born too soon.

Breathing easier

Cathy Delaney

It was Christmas Eve, said nurse Cathy Delaney.

A full-term baby was in shock from an infection, said Delaney, one of four neonatal transport nurses at Wiser. It was a one-hour and 15-minute drive back to Jackson and Delaney had to resuscitate the baby over and over the entire way.

“I got down on my hands and knees and prayed the baby wouldn’t die on Christmas Eve,” Delaney said.

The baby lived through Christmas Eve.

“And then it was, ‘Please don’t take this child on Christmas Day,’” she said. The prayer grew longer and longer, and so did the child’s life.

“After two weeks,” Delaney said, “the baby went home.”

All newborn babies’ chances grew, particularly preemies’, with the use of oxygen and the development and improvement of breathing machines and ventilators that take over for their almost powerless lungs.

Then, there was artificial surfactant – a real godsend, Mullins said. Administered to the baby through a breathing tube that enters the windpipe, it mimics a natural substance that helps keep the lungs inflated.

In December 2013, the journal Pediatrics reaffirmed that surfactant “reduces mortality … and lowers the risk of chronic lung disease or death at 28 days of age.”

It began making a “radical difference” in survival rates by the early 1990s, Mullins said.

But long before that, near the beginning of the renaissance in neonatal care, the Junior League of Jackson donated a special $45,000 ambulance to the City of Jackson. Dedicated to moving babies, the “Neonatal Cradle” could hold an incubator, nurses with specialized training, IVs, a breathing apparatus and more.

It was 1979, the year that neonatal transport at UMMC really got moving.

The donated ambulance transported premature and high-risk newborns from all over the state to the Medical Center and other Jackson-area hospitals that could deliver specialized care.

Over the years, members of UMMC’s transport team have also traveled to just-over-the-border spots in Louisiana, Tennessee, Arkansas and Alabama.

By the 1990s, many of their patients, almost as soon as they were born, were taking their first helicopter rides. Today, UMMC’s flight program, AirCare, shuttles approximately 40 percent of these babies to Jackson – when the distance (more than 50 miles one way), the weather and the urgency permit.

“We fly and we drive,” Davidson said.

Inside the copter and the two ground ambulances that are now available at all times are incubators, medicine, heart monitors, breathing machines, IVs and CPR equipment.

“Each one is a mobile intensive care unit,” Delaney said. “We take intensive care to the patient.

One of the newer ambulances to transport babies and children around the state awaits the next call at the hospital.

“In the transport, it may be simple things: keeping the babies warm, giving them oxygen and fluids. But some community hospitals aren’t equipped for that.”

A lot of hospitals in this state don’t handle deliveries, Mullins said.

“They are good people doing the best they can, but they don’t have babies.”

So, in such cases, even mothers of some full-term babies come to UMMC, or try to, Mullins said. Some don’t make it here in time; they’re born in a community hospital’s emergency room or at home in a distant town.

The number of neonates (babies who have been under hospital care since birth) transferred each year from other hospitals to Wiser ranges from 250 to 450.

When neonatal transport started, UMMC was the only place in the state with specialized care for preemies. Now, other medical centers offer it as well, Mullins said. But this is still the place for infants who need such care as heart surgery: UMMC has the only pediatric cardiac surgeon in the state.

“And when there are certain complications of the intestines, and certain infections, it’s a matter of hours before they die,” Mullins said. “They need immediate surgery.”

And they need the transport team to take them to the surgeon.

Patients are a virtue

AirCare I, one of two emergency helicopters, is essentially a flying intensive care unit.

As for the 4,000 babies Miller saw in her career, not all of them were sick for long, she said.

“Some we transported back to community hospitals to complete their stay and be closer to their families.”

That’s what she was doing years ago on the day she helped bring those waiting parents their baby, after that 100-yard slog through the mud.

But the marathons through muck, over ice and under darkening clouds didn’t bother her, she said.

“That was our job. You never got tired of traveling. You want to do what the babies need. That’s what drives you.

“We had a good arrangement, where if you felt you got too tired to be safe and effective, you could call a co-worker and say, ‘I’ve got to pass the torch on this one.’

“Of course, on the way there, there was no patient, so I napped in the ambulance quite a bit.

“But my husband could never figure out why I would never enjoy a Sunday drive.”

UMMC Nurse Nancy Park helps Jackson Fire Department driver Pat Kelly move an infant from the Neonatal Cradle into the Children's Hospital in 1983.

Dr. Phil Rhodes, left, professor emeritus of pediatrics and former division chief of newborn medicine, lifts an infant into a fixed-wing airplane with help from a Jackson Fire Department driver.