A Series of Doors

Dr. Hans-Georg Bock retired in July after 31 years at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, but he didn’t dance out the door. In fact, just 10 days before his final day at work – his office strewn with creaking chairs and files and books – he still hadn’t packed a single thing.

Bock’s next chapter sees his return to Texas, a place he and his wife left 31 years ago to come to Mississippi with much the same reluctance he feels now about leaving the state he’s called home all that time.

In a strange mishmash of wistfulness and rationality, he recalls that all the chapters of his life – all the metamorphic moments – unfolded in much the same way.

“I never was in a position where I made a decision; doors just opened. That’s how God works,” Bock said. “It’s kind of been the story of my life. Doors just kept opening and the best door was coming here to Mississippi.”

The earlier chapters in Bock’s life include a childhood in Tullahoma, Tennessee, a little town due southeast of Nashville where his father worked for Arnold Engineering. Later, Bock earned his bachelor’s degree in molecular biology at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

He remembers not knowing what he wanted to do during his senior year at Vandy, so when a door opened there in the form of a scholarship to its combined M.D./ Ph.D. program, he walked through. He completed his joint degree in 1977.

The chapter in which Mississippi became the setting began in 1983, after he completed a pediatric residency and a pediatric genetics fellowship at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

It was then that another door opened for him – a position in UMMC’s Department of Preventive Medicine. Knowing very little about Mississippi, he accepted, mostly, he says, because of the friendly people.

“It was hard not to fall in love with Mississippi,” he said. “You can’t say that about every place.

“Mississippi and the Medical Center welcomed me with open arms and I’ve never forgotten that. I’ve always been very appreciative of that. You don’t get that very often in the world today.”

Bock’s arrival at UMMC came at a time when the Division of Medical Genetics saw just a couple of patients a week. That number has risen sharply in recent years to upwards of 40 patients a week, thanks to increased coverage of genetic anomalies by the media and on Internet-based sources.

“People often will see that and say, ‘That sort of looks like my child,’ and then they come in and they want counseling, evaluation, testing for something because they saw it on a program.”

Bock says the knowledge base has mushroomed, leading to a tremendous increase in the number of self-diagnoses.

But there are still cases like that of Emmalyn Hudson of Columbus. She came to be Bock’s patient at just 6 days old, accompanied by terrified parents with more questions than answers.

Emmalyn was five weeks premature, but her parents, Shannah and John, still believed they took home a healthy, happy baby. That changed on their second night home when they received a call at 10:30 at night from the local hospital where she was born.

Emmalyn's routine heel stick screening test had come back positive for “something,” and although hospital staff wouldn’t tell the Hudsons what it was, they insisted Emmalyn be brought back to the hospital immediately.

Shocked and confused, the Hudsons were told to pack a bag because Emmalyn would be transferred to Batson Children’s Hospital in Jackson the next morning.

“That call totally shook our world and turned everything upside down,” Shannah Hudson said.

The next call was around midnight from Bock, who explained the heel stick revealed a rare genetic metabolic disorder called Glutaric Aciduria Type 1. He called again when they were en route to Jackson the next morning.

Then he literally met them at the door.

“We finally got there, pulled up to the ER and saw a man striding across the lobby and he just grabbed her up and said, ‘Mom, come with me.’ I don’t know many doctors that will call when you’re on the way to the hospital and literally meet you at the doors. He’s one in a million.”

Emmalyn’s disorder is characterized by her body’s inability to break down certain proteins properly. If left untreated, GA1 could cause brain defects or even death. Thankfully, Emmalyn, who turns 4 in September, has a good prognosis.

Shannah believes “Doc Bock,” as Emmalyn calls him, helped get them this far and says the whole family was devastated to learn of his retirement.

“He’s like an extended part of our family,” Shannah said. “We will miss the personal connection and contact that we have with him.”

“It’s the family who’s living it. I’m not taking any of the credit for this,” Bock said. “They get all the credit. Our job in this process is to strengthen them so they can rise to the occasion.”

This sense of humbleness and consideration has permeated Bock’s time at UMMC.

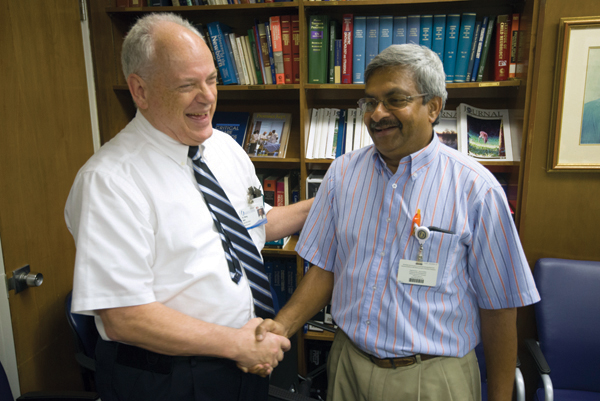

Dr. Omar Abdulrahman first met Bock as a second-year medical student taking Bock's genetics course. Abdulrahman says that while he learned a great deal about genetics that semester, the concept that Bock embodied was the idea that physicians can have great compassion for their patients.?

“He always talked about genetic disorders from the perspective of the patients and their suffering, and how we as healers could always impact their lives even if we couldn’t cure them,” Abdulrahman said.

He recalls witnessing Bock reach into his own pocket and hand over a five dollar bill to a patient's family to help pay for their return to a critical follow-up visit.

“I’d never seen that before,” Abdulrahman said. “Even though the five dollar gift was only a small amount, the family saw this gesture as an act of human kindness by their child’s doctor who really cared for their child as if they were his own.”?

For his part, Bock says he has benefited more than his patients and that these relationships – with his patients and with his coworkers – are what he will miss most.

“It’s all about people,” he said. “It’s not about books you wrote or awards. It’s about the people you serve. I’m going to miss the people.”